In 1931 Albert Einstein gave a grand piano as a birthday gift to his sister Maja, at the time living in Quinto close to Florence. Before her forced departure for Princeton in 1939, Maja left this piano with the German artist Hans‐Joachim Staude, who was also living in Florence. On 23rd June 2016 the piano was given to the astrophysicists of the Arcetri Observatory under the aegis of the science festival ‘Notti d’Estate’ organized by Paolo Tozzi.

On that festive occasion – at sunset with the famous view spread before us – we listened to the history of this instrument entwined with the fates of very different personalities. The pianists Luisa Valeria Carpignano and Ferdinando Mussutto played a piece ‘à quatre mains’ conceived by Antonio Staude. These are the notes used for this account.

Dear colleagues, dear friends,

I want to tell you a story about the grand piano that Albert Einstein gave to his sister Maja in 1931 and which today, after many vicissitudes – of the piano and people involved – has come to rest up here, entrusted to the astrophysicists of Arcetri (Fig. 1). It’s a story of love of art and culture in general, of love of Florence and of one’s country, entwined with the most paradoxical and terrible events of those years. I will simply give the chronology of the events and I will start from a very long time ago.

-

Fig. 1:

The Arcetri Astrophysical Observatory

seen from the Torre del Gallo [GFDL]

I

In 16th century Venice, the Jewish family Del Banco was one of the richest and most powerful of the city. To escape the persecutions of that time, the Del Bancos emigrated first to Bologna and then, in the 17th century to Warburg, city of the Hanseatic League in Westphalia, halfway between Cologne and Hanover, taking its name as their own. Later on the Warburgs moved to Altona (Hamburg) where in 1798 the brothers Moses and Gerson founded their private Bankhaus Warburg.

1879: Two very young brothers from this dynasty come to an agreement that was to have great repercussions; Abraham Warburg (1866-1929), called Aby and aged just 13, the eldest son and passionate about books, forfeits his right to take over the family bank to Max Warburg (1867-1946), his younger brother aged 12. In exchange Max promises to provide Aby with all the books he ever wants.

Aby devotes himself to studying Renaissance art and culture. In 1898 he comes to Florence (Fig. 2), where he participates in the Florentine and international intelligentsia which at that time resided in this city and on these hills.

-

Fig. 2: Florence seen from Arcetri.

Monte Morello in the background

[Roberto Baglioni]

Aby describes himself as: “Jew by birth, Hamburger at heart, Florentine in spirit” and soon commits himself, with others here in Florence, in developing a private centre for Renaissance studies. Founded in 1897, it was the precursor of the Deutsches Kunsthistorisches Institut, called ‘the Kunst’ by the Florentines, today the Max-Planck-Institut for Art History, with premises in Via Giuseppe Giusti 44.

1902: Aby, having returned to Hamburg, starts to build the Warburg Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek financed by his brother Max, a private study centre devoted mostly to the Italian Renaissance, which was to maintain a special relationship with the Florentine ‘Kunst’.

II

1904: In Port‐au-Prince my father HansJoachim Staude, called Hans-Jo, is born, second son of the trader Hans‐Carl Staude (1872‐1933) from Halle in Saxony-Anhalt, arrived in Haiti for work, and of Elsa Staude (1875-1962), née Tippenhauer, who has a Hamburger father and French mother. Elsa had been born in Haiti, where the maternal French branch of her family had lived for generations.

1909: Elsa moves to Hamburg with her sons Gustav and Hans‐Jo to give them a good bourgeois education. HansCarl continues his work, mostly in Haiti.

1910: In Hamburg Max Warburg takes over, as agreed 31 years earlier with his brother Aby, the management of the Bankhaus Warburg and soon makes it one of the major German private banks, an authentic global player. He is also directly involved in the social and political life of Hamburg, a city-state largely independent of the Kaiser’s government in Berlin.

1919: Max participates in founding the University of Hamburg. Aby becomes a professor of Art History there and soon it attracts luminaries such as the philosopher Ernst Cassirer, the art historians Gustav Pauli and Erwin Panofsky, the Orientalist Hellmut Ritter, the classical philologist Karl Reinhardt and the Byzantinist Richard Salomon.

III

Meanwhile Maja Einstein (Fig. 3), Albert’s sister, born in 1881 in Munich, grows up first in Milan and then in Aarau in Switzerland, where she obtains a teacher’s diploma in 1905. She studies Romance languages in Berlin, Paris and Berne, where she graduates in 1909.

1910: Maja, because she had married – Paul Winteler, lawyer and amateur painter –, loses her teaching licence since in Switzerland at that time woman teachers had to be unmarried. Maja and Paul give up their work and first settle in Lucerne then, with little money, they go to live in Florence in1920.

1922: With the help of Albert Einstein, the Wintelers buy an old farmhouse at Quinto, in the foothills of Monte Morello (see above, Fig. 2). They call it ’Samos’ because it reminds them of mythical Greece (Fig. 4).

-

Fig. 3:

Maja Einstein

(1881-1951)

-

Fig. 4:

Maja in front of her house ’Samos’ in Quinto

In this simple farmhouse Maja loves playing on her old piano while Paul paints the surrounding countryside; they play chess together and, always short of money, cultivate a few but intense Florentine and international friendships. Maja often plays the piano ‘à quatre mains’ with some of these friends.

Here I would like to give some comments that Antonio Staude made in presenting the programme of the piano concert performed in Arcetri on 23rd June: “Maja called this musical practice ´Vierhändern´: a rather unusual German verb – at least in today’s parlance – that describes in one word playing the piano ‘à quatre mains’, also rendering that particular intimacy and passion for music linked to a particular interaction with guests arriving in ´Samos´ from various European countries. In her diary Maja compared playing a transcription of Beethoven’s string quartet op 59 ‘à quatre mains’ to a fitting ´dessert´ for rounding off a dinner among friends. In this context the music was seen as a source of vital energy and intensity.

At the beginning of the 20th century, before gramophones and stereos entered our homes, playing transcriptions for the piano –a tradition begun in the previous century by Franz Liszt and continued for example by Ferruccio Busoni – was a way of approaching every type of music from church hymns to opera, from ensembles to the great symphonies. Without going to concerts, less frequent than now and not always easy to get to, performing these works enabled creative exchanges and gave a sense of something that entered the music from life and, by playing it, returned to inspire and surprise us.

Among the pieces in the programme, the opening movement of Symphony No. 6 in F major – the Pastoral – by Ludwig van Beethoven, completed in 1808, stands out. The composer, already suffering from deafness, liked to retire to the country in close contact with nature. Participating in the rural life by following its rhythms filled him with great joy since it opened the way to inner peace. Beethoven said that the Sixth Symphony is “more the expression of feeling than painting” and this is the spirit that permeates the music which, like the works of Bach, Mozart and Brahms we will hear, could well have been part of the repertory of Maja and her friends”.

IV

Meanwhile in Hamburg, Hans‐Jo is also playing the piano; he does it so well that everyone predicts he will be a pianist when he grows up (Fig. 5). But in 1921, when he is just sixteen, in his secret diary he solemnly promises to himself that he will become an artist. In the years 1923-1925 he socialises with his peers in the Warburg home, where art and Italy is part of the cultural atmosphere.

At school Fritz Rougemont (1904‐1941), who was to become an art historian and translator of Petrarch at an early age, is Hans-Jo’s best friend. In their conversations, they focus on the upheavels going on at those times in the arts and literature, which are reflected in the magazine “Die Werdenden” (“Those who are becoming”), edited by Hans-Jo and his also painting friend Karl Bröcker and illustrated by their own woodcuts. (Fig. 6)

Fritz is already part of the Warburg scene and in 1923, immediately after leaving school, he follows Aby to Florence preceding his friend Hans‐Jo, where he is soon introduced to Maja Einstein and Paul Winteler and where he studies for some years.

The forty-two year-old Maja takes the brilliant youth under her wing and mothers him (Paul doesn’t seem to approve of this relationship, see Fig. 7.) Maja writes of him: “Fritz has a fine and good soul. He’s the only person I’ve met so far who, as soon as he realizes I’m embarrassed or in pain, immediately does all he can to relieve it. This, especially in such a young person, is truly a rare quality”.

V

1924: It is not known how, but in the summer the nineteen-year-old Hans‐Jo finds himself alone with Albert Einstein, now a world-famous Nobel prize laureate, on Travemünde beach near Lubecca. Perhaps the meeting was arranged by his friend Fritz Rougemont.

There are two different versions of this meeting between the two men, so different in status, which are probably two equally true parts of the same story. About what my father told me of this conversation when I was a young boy, I remember this:

Einstein: And you, young man, what do you do?

Hans-Jo: I… would like…with my painting… to give an image of the world.

Einstein (thoughtful): …Well…in the end…we want the same thing.

In 1963, Hans-Jo talks about this to Tiziano Terzani, who had just married my sister Angela. He immediately made this note, that Angela will read to us now:

Einstein: It’s difficult today for a young artist to choose a path to follow. Among so many movements, which one should you make your own?

Hans-Jo: It’s not difficult for me. I do what I feel and I’m determined that I’ll always do it.

Einstein: It’s true, we often remain fixed to our ideas out of stubbornness. I can understand and appreciate the theories of my adversaries – and it’s only out of stubbornness that I continue to uphold mine.

Hans-Jo to Tiziano: “I once heard him improvise on the piano: sweet, naive, almost infantile, but beautiful”.

VI

1925: On Easter Day Hans‐Jo, just turned twenty, arrives in Florence for two weeks and remains there almost all his life; his new Florentine friends soon start to call him Anzio, and he adopts the name. He immediately meets Fritz Rougemont, who introduces him to the Wintelers (Fig. 8). Maja also takes him under her wing and they soon start playing the piano ‘à quatre mains’

and Paul Winteler

From 1926 to 1933 my grandmother Elsa Staude used to come to Florence from Hamburg to visit her son Anzio. Soon, she also met

Meanwhile Fritz Rougemont, having returned to Hamburg, commits himself totally to the Kulturbibliothek Warburg, so much so that he is asked, with Gertrud Bing, to edit an initial collection of Writings by Aby Warburg, who died in 1929, that were published as early as 1932.

1930: In Florence Anzio takes up residence in an old house in Via delle Campora 30. (Fig. 10)

-

Fig. 8:

At ’Samos’: Maja Einstein, Anzio, his uncle

Georg Staude,

on a visit to Florence,

and Paul Winteler

-

Fig. 9:

Maja Einstein and

Elsa Staude

(ca 1933)

-

Fig. 10:

We lived on the first floor of this house,

from whose windows you can see the Arcetri

domes, for a total of 71 years, up to 2001.

(The Photo was taken in the Fifties)

1931: In ’Samos’ Maja’s old piano ends its days. Maja, desperate, hasn’t the means to replace it. But in Berlin Albert buys a Blüthner grand piano, made in Leipzig in 1899 and recently restored, and sends it to Quinto as a birthday gift for Maja. Maja’s letters demonstrate her boundless joy at the news of the purchase:

“Ah, how blissful life is! Even more so because yesterday I had the exciting news that my brother has personally chosen a Blüthner piano for me, and I’ll soon be able to welcome it here in ’Samos’. Isn’t he a perfect brother, over and above all his other qualities?”

And after the arrival of the piano:

“The piano has arrived! And what a piano! If you could hear how it sounds! It’s voice is fantastic, so flexible… I’d never have dreamt of it! Finer than Anzio’s Bechstein: if you could hear how it sounds – like a nightingale and like an organ! Like flutes and like violins! Anyone who can make it sing with all its voices would make music from heaven, hell and all the rest! It really makes me feel blissful!”

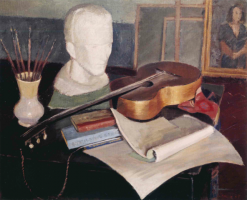

Those years in Quinto, up to the first days of 1939, will be remembered as an orgy of piano ‘à quatre mains’ and – more in general – of the fusion of all the arts, allegorically illustrated in a still life by Anzio (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11:

Hans-Joachim Staude:

Painting, Sculpture, Music and Poetry.

Oil on canvas,

1937

VII

1932: in November Albert Einstein goes to America for a conference tour.

1933: in January Adolf Hitler comes to power in Berlin. As a result….

– Albert Einstein will never return to Germany. He is soon called to Princeton and remains there for the rest of his life.

– Fritz Rougemont, Anzio and Maja’s sensitive friend, converts to Nazism: the friendship between him and Anzio ends ex abrupto, with great pain on Anzio’s part. Only Maja refuses to believe it and in her letters to common friends continues for years to defend Rougemont fiercely until even she has to admit his evident devotion to the Nazi cause.

– The Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg is saved from the clutches of the Nazis and relocates from Hamburg to London, where it is re-established with the name Warburg Library, later Warburg Institute, a kind of Princeton Institute for Advanced Studies, which still today focuses on art and culture of every kind and provenance.

– My grandmother Elsa Staude becomes a widow and moves to Florence to live with her son Anzio. Maja is very happy and says this about the death of my grandfather: “Every cloud has a silver lining!”

– Finally, again in 1933, Max Warburg is expelled from the board of directors of the Deutsche Reichsbank, on which he had sat since 1924; he was to remain a member of twelve other boards of directors until 1935.

1938: Max is also forced to resign as a director of the Bankhaus Warburg, to sell it and to emigrate with his family to America, where he still has numerous banking contacts and where he will die at almost eighty years of age in 1946. He takes leave of his 200 employees remaining in Hamburg with a long speech that ends with these words: “I wish you success in your work, for the good of the city of Hamburg and for the good of Germany.”

In the same year, Anzio travels from Florence to Hamburg to marry Renate Moenckeberg, the friend of his youth: the two had met in 1925 at a carnival party in the Warburg home. Renate comes to live with Anzio and grandmother Staude, and later with their children Angela and Jakob, in Via delle Campora 30.

1939: the racial laws had now come into force in Italy as well. As a result, in February Maja leaves the Blüthner in Anzio’s care in our house and travels to Switzerland with Paul intending to go together to Albert in Princeton. But since Paul is a Swiss citizen he cannot obtain a visa for the United States and so Maja leaves by herself, certain she’ll be able to return with him to ’Samos’ in a few months time. War breaks out and in 1941 Fritz Rougemont, who as late as 1938 had sent Maja a booklet of his fine translations of Petrarch, falls as a convinced Nazi on the eastern front.

1942: Anzio in Florence is called up in the Wehrmacht with the rank of private soldier: he remains in Italy with the function of Italian-German translator, first in Rome and then in Verona. He was never capable of saluting his superiors as the rules dictated, and was exonerated from taking up arms because of his age and incapacity.

Here it must be said that Maja Einstein and Paul Winteler weren’t the only family members to live in Italy. Robert Einstein, cousin of Albert and Maja, lived with his wife Nina Mazzetti, daughters Luce and Annamaria and nieces Lorenza and Paola Mazzetti, orphan daughters of Nina’s brother, first near to Perugia, then in a country villa in Rignano sull’Arno just outside Florence.

1944: on 3rd August, as the German army retreats to the north and the front passes through Florence, a terrible massacre takes place in Rignano: a German officer with his men destroys Robert’s house, who is absent, killing Nina and their daughters. It seems that the murderers of Robert’s family are really aiming at the far-away Albert whom they consider a traitor as well as a “Jew”; the nieces Lorenza and Paola Mazzetti are saved since “not of the Einstein family”. Robert commits suicide a year later and now Lorenza, who is present with us now, will tell us her story.

1945: during the German retreat (March/April), close to Bolzano, at night and wearing his private’s uniform Anzio manages to flee from the Wehrmacht. He reaches the house of friends, changes out of his uniform and stays in Italy. In August he returns to his home in Florence and starts painting in his city again (Fig. 12).

-

Fig. 12:

Anzio painting in the square in front of Porta Romana.

(Anni Cinquanta)

VIII

1948: Elsa Staude travels from Florence to the United States to see, after many years, her other son Gustav who lives there. She takes the opportunity to pass by Princeton to see her friend Maja, already very sick, for the last time (Fig. 13).

1951: Maja dies in Princeton, without ever having seen again either her husband Paul or her beloved ’Samos’. Paul dies in Switzerland the next year. My grandmother had written about her: “I now know what Maja’s particular fascination for me consists of: it’s this absolute verity with which she lives; no doubt ever arises about acts or her words – her heart and her mind are like crystal. How much good such a person does!”

1955: Albert dies in Princeton.

1957: A very distinguished gentlemen comes to the door of our house in Via delle Campora 30: it’s Vero Besso (1898-1971), the son of that Michele Besso who first was a colleague and close friend of Albert Einstein during the time they both worked in the Patents Office in Berne and later, through his marriage to Anna Winteler, Paul’s sister, also his relative. Vero Besso is the heir to ‘Samos’, he lives in Florence and is managing Einstein’s legacy in Italy. He asks my father about the piano: Anzio receives him the greatest courtesy, takes him to the music room and, with a trembling heart, talks at length of the happy years in ’Samos’. Vero Besso listens attentively. Then he says: “I see it’s not possible“, and he goes away, leaving the piano where it is. So Einstein’s piano stays with Anzio, who will play it until the end of his life in 1973 (Fig. 14).

-

Fig. 13:

Elsa Staude and Maja Einstein

in Albert’s house in Princeton

-

H.-J. Staude al pianoforte nella sua casa

in Via delle Campora. (Anni Cinquanta)

IX

2001: after the death of my mother we leave le Campora. The piano moves with us to Mosciano above Scandicci in a simple house among olive trees, on the hills at the southern edge of the Florence basin and opposite Quinto, and thus with a view of ’Samos’. There in the summer, our sons Lorenzo and Antonio play it.

2015: our friend Francesco Palla, a Florentine astronomer and former director of Arcetri, comes to visit us in Mosciano, sees the piano, listens to its story and suggests storing it in Arcetri, for the use of the piano-playing astrophysicists and for astronomic-musical events.

Francesco unexpectedly left us not long ago, but today his idea will be carried out. The piano, recently renovated by the tuner Simone Bussotti, here with us today, has gone to the Observatory and we have signed the commodatum agreement that will regulate its presence in Arcetri (Fig. 14). Filippo Mannucci, the current director of Arcetri, commented on this photo: “Apart from the biros, we look exactly like two heads of state!”.

So the piano will remain up here in view of Quinto (which is over there at the foot of Monte Morello) and of the house in Via delle Campora (Fig. 15): in this new stage in its history it will be entrusted to our astrophysicist friends – to Einstein’s young colleagues!

-

Fig. 15:

Filippo Mannucci and Jakob Staude sign the commodatum

agreement for Einstein’s piano

[Paolo Tozzi]

-

Fig. 16:

The house in Via delle Campora 30,

with its large tower, seen from Arcetri

[Enrico Pinna]

Bibliographical notes

Franziska Rogger, Einsteins Schwester. Verlag NZZ, Zürich 2005

Hans-Joachim Staude: www.staude.it (trilingual internet site)

Lorenza Mazzetti, born in Florence in 1928, is an artist and film director. Immediately after the war she went as a young girl to London, where she attended the Slade School of Fine Arts. Her first film “K” (1953), freely based on Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, is considered the precursor and manifesto of the Free Cinema avant-guard movement. She has also written various books, including Il cielo cade (1962), in which she recounts the tragic events in Rignano, and Diario Londinese (2014). Since 1956 she has been living and working in Rome as a writer and dramatist.

(Translated by Sarah Nodes)